Zeroing a rifle is always fun. Seriously, it used to be something I dreaded because I wasn’t very good at it. After becoming a gun writer, though, I’ve zeroed so many optics and guns that I find it to be a bit enjoyable. It’s like solving a puzzle, and the little dopamine hit from hitting the target exactly where I want to is fantastic. There are lots and lots of thoughts on zeroing rifles. The most common sense thing to do is zero at the range you plan to shoot.

However, how do we know the range we plan to shoot? It’s not always so well-defined. While it’s nice to think you’ll always be shooting at 100 yards, that’s not always the case. This leaves us trying to find a zero that can work at many ranges. One of the most common methods is to use a Battle Sight Zero like the famed 50/200.

Today, I wanted to explore the famed 50/200 BZO, its pros, its cons, and why or why not it might be the best option for you and your rifle.

What’s the 50/200 Yard Zero

To answer that question, we have to define a Battle Sight Zero, aka the BZO. The military is a big believer in the BZO and defines it as:

The term battle sight zero refers to the combination of sight settings and trajectory that greatly reduces or eliminates the need for precise range estimation. It further eliminates sight adjustment, holdover, or hold-under for the most likely engagements. Battle sight zero is the default sight setting for a weapon, ammunition, and aiming device combination.

An appropriate battlesight zero allows the shooter to accurately engage targets out to a set distance without an adjusted aiming point. For aiming devices that are not designed to be adjusted in combat or do not have a bullet drop compensator, such as the M68, the selection of the appropriate battlesight zero distance is critical.

The 50/200 yard zero is designed for an AR-15 with standard .223/5.56 ammunition. It may work for other calibers and rifles, but I know it works for the AR series of rifles in 5.56. The 50/200 yard zero works with the majority of bullet weights. It was designed with the old 55-grain M193 in mind, but it works well with 62- and 75-grain projectiles as well.

The 50/200 yard zero is a 50-yard zero that postulates that a 5.56 round zeroed from AR-15 with a standard height sight of 2.6 inches will have an acceptable zero from 50 to 200 yards with the need for any adjustments. The 50/200 isn’t the only battle sight zero out there, but it’s one of the most common.

How does it work?

Whenever you shoot a gun, the earth’s gravity instantly affects the bullet’s trajectory, pulling it downward. You might not notice it, but when you fire a rifle, you’re more or less arcing it upward. The barrel is canted upward due to its sight alignment. The projectile starts moving at an upward angle to resist the effects of gravity to increase the rifle’s range. If you fired the gun in a perfectly level configuration, the bullet would hit the dirt quite quickly.

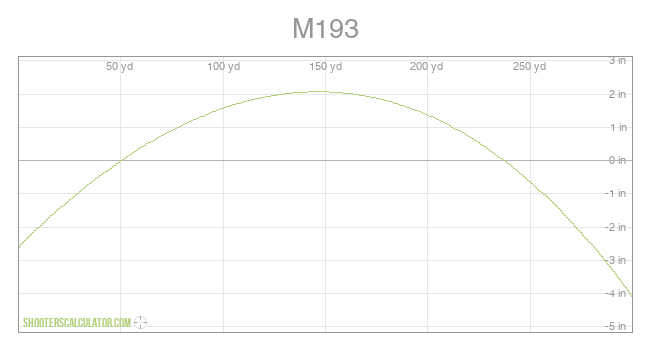

The bullet will travel upward to a peak or apogee and then begin to descend. This creates our trajectory. When you use a 50/200 yard zero, the sight line and the bullet’s path align perfectly at 50 yards. At 50 yards, the projectile isn’t above or below the reticle. If it were above or below, we’d indicate that with a + or – and a number to follow. Since it’s ‘zeroed’ at 50 yards, it’s represented by a 0.0.

How It Works In Detail

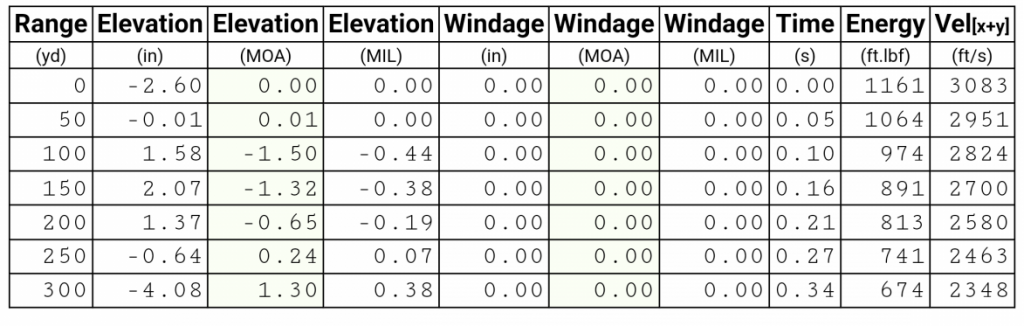

Beyond 50 yards, the projectile will either rise or fall below that 50-yard zero. This creates a path that doesn’t guarantee a perfect zero. For example, if we pull the ballistic tables of a 50/200 yard zero with 55-grain ammo, we have our 0.0 at 50 yards, and at 100 and 150 yards, we see a slight rise in the projectile because it’s still traveling along its upward arc.

At 100 yards, the projectile is approximately 1.5 inches high. At 150 yards, the projectile is approximately 2.1 inches high. When we get to 200 yards, the round does fall but still lands about 1.5 inches above your point of aim. When we reach 250 yards, we see a decline, bringing the round approximately .70 of an inch below your point of aim.

Wait, That’s Not a Zero

You’re right; it’s not a true zero when you get 200 yards. In fact, it’s technically more accurate at 250 yards. The 50/200 zero isn’t a true zero. It’s only really zeroed at 50 yards. However, the margin of error at 200 yards is fairly minimal, especially when you factor in ammunition accuracy.

The 50/200 yard zero is ‘good enough’ between 50 and 200 yards. To be honest, it’s good out to 250 yards. It’s not a perfect zero by any means, but it does work when our concern is landing accurate enough hits at a variety of standard engagement ranges.

When you think about your accuracy needs, the 50/200 yard zero is practical rather than precise.

This type of zero is referred to as a maximum point-blank range. From 50/200 yards, we will get an acceptable hit on a fairly small target. Let’s say the acceptable target size is an ISPC A-zone. The A-zone is a 6.5 x 11-inch rectangle. You can aim dead center from 50 to 200 yards and land a hit inside that box.

Why Pick the 50/200?

The Marine Corps uses a 36/300 yard zero and a 25/300 yard zero. With that in mind, you might ask why you wouldn’t want to zero with a BZO that gives you a longer effective range. You get a fairly flat zero from 50 to 200 yards, which isn’t the case with the 36/300 and 25/300. With those rounds, you get deviations over four inches between 100 and 200 yards. That’s a good bit of deviation and might be a bit much for some shooters.

The 36/300 yard zero works well with magnified optics. The 50/200 excels with red dots that allow for quick, instinctive shooting at various ranges. You might not get much of a choice. Some manuals will specifically advise you to use a certain zero over another. That will likely be your best bet, especially if the optic has a ballistic drop reticle.

The 50/200 yard zero represents a very easy and measured zero that gives you a nice flight trajectory to the target. I tend to stick with it even after my history of being in the Marine Corps and using the 36/300 for years. I find it quick, accurate, and easy to use.

What’s your preference? Your opinions? Share below!

Read the full article here